Game Boy Post Processing shader for Unity

There was a small talk on making a Game Boy post processing shader on Unity dev chat on Discord (http://fromsmiling.tumblr.com/post/95495323142/tutorial-game-boy-shader-post-processing), but it‘s using a Shader Forge for a lot of post processing steps and uses a not very optimized version of pixelization. Also, doing some research, I haven’t found any drag-n-drop solutions for this seemingly simple effect (a few people sell it for around 1$-5$ for Game Maker or as plain shaders,)

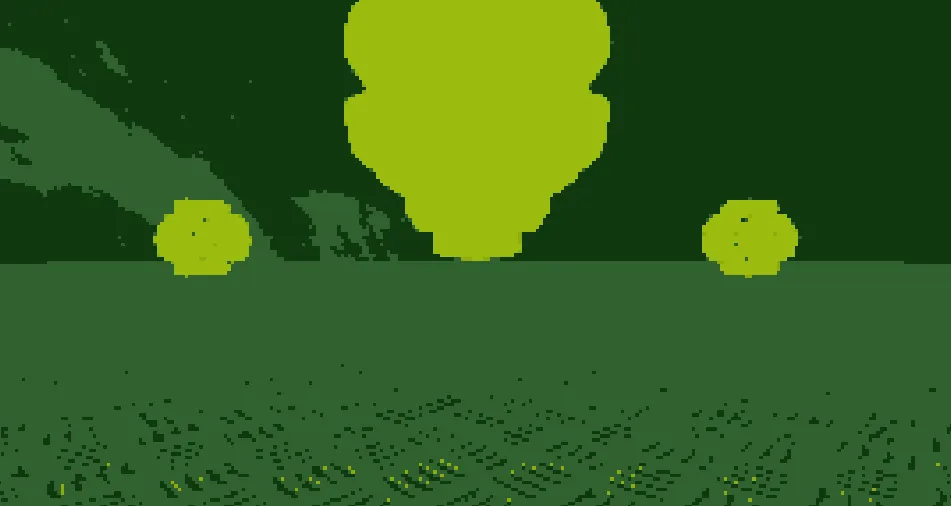

So here we go. Before and After (scene from NatureStarterKit2):

The post effect is simple:

- Downscale it so it becomes 144 by height (the original Game Boy screen height)

- Find pixel brightness (luma)

- Posterize it (reduce to 4 colors)

- Using the logic from Taylor Bai-Woo, color this posterized version to four original Game Boy colors

Down we go.

To achieve pixelization effect, we can either go with some complicated UV truncation logic and calculate everything in full-screen resolution, or just make a smaller target render texture. It will save us some work and will also be faster to calculate.

Create a new C# Script called Gameboy. Let’s start with creating a downscaled render texture.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

using UnityEngine;

public class Gameboy : MonoBehaviour

{

private RenderTexture _downscaledRenderTexture;

private void OnEnable()

{

var camera = GetComponent<Camera>();

int height = 144;

int width = Mathf.RoundToInt(camera.aspect * height);

_downscaledRenderTexture = new RenderTexture(width, height, 16);

_downscaledRenderTexture.filterMode = FilterMode.Point;

}

private void OnDisable()

{

Destroy(_downscaledRenderTexture);

}

}

We will need a private RenderTexture field. We create this RenderTexture in the OnEnable function so we can safely Destroy it when we disable our effect.

We consider the Height of our screen to be the constant value of 144 pixels. But the width will depend on aspect ratio (it won’t always be 160 like in original Game Boy), so we need to calculate it. To do it, just multiply the camera aspect ratio value by height. We also need to set its filterMode to Point so it doesn’t try to smooth the pixels out.

And don’t forget to Destroy it in the OnDisable function.

Now we need to actually do some post processing with it. Let’s start with the simple stuff — an Identity shader that will just copy current pixel values to another target Render Texture. Why do we need it? Because using a simple way of Post Processing in Unity requires us to use the passed destination Render Texture, or it will not render anything. There are, of course, different ways to handle it (I will write about it in some other post), but for simplicity lets just use OnRenderImage for now.

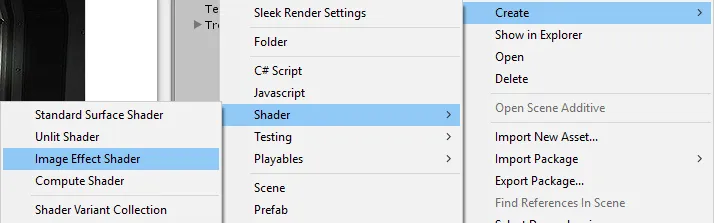

Create a new Image Effect shader in Unity and put it somewhere:  Creating an Image Effect Shader

Creating an Image Effect Shader

Now open it and rename it to Identity, and change the fragment shader logic to the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Shader "Identity"

{

...

SubShader

{

...

Pass

{

...

float4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

float4 col = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

return col;

}

}

}

}

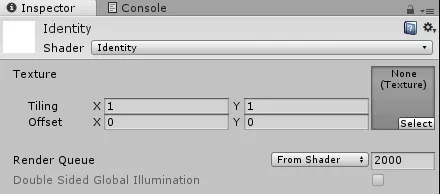

Now create a new Material and change its shader to Identity.

It misses a texture, but don’t worry, it will be filled automatically.

Let’s add an Identity Material reference to our Gameboy script and add an OnRenderImage function where we use this material to blit the source texture to the target.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

using UnityEngine;

public class Gameboy : MonoBehaviour

{

public Material identityMaterial;

private RenderTexture _downscaledRenderTexture;

private void OnEnable()

{

var camera = GetComponent<Camera>();

int height = 144;

int width = Mathf.RoundToInt(camera.aspect * height);

_downscaledRenderTexture = new RenderTexture(width, height, 16);

_downscaledRenderTexture.filterMode = FilterMode.Point;

}

private void OnDisable()

{

Destroy(_downscaledRenderTexture);

}

private void OnRenderImage(RenderTexture src, RenderTexture dst)

{

Graphics.Blit(src, dst, identityMaterial);

}

}

Notice lines 7 and 23–26.

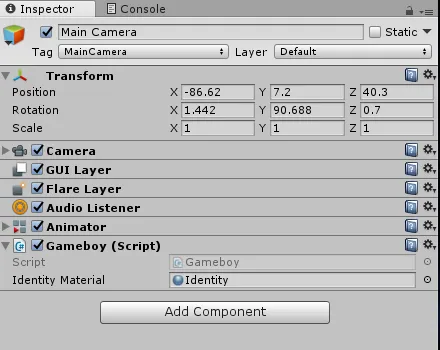

You can now add this script to the Camera and link an Identity material there:

This won’t have any visible effects though as the Identity image effect does nothing. You’ll get why we need it a bit later.

The effect itself

Finally we can start making the effect itself.

First, create a new Image Effect Shader like you did for the Identity shader and rename it to Gameboy. We will need four additional color parameters. I’ve done some research and here’s the original Game Boy colors (https://designpieces.com/palette/game-boy-original-color-palette-hex-and-rgb/):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Shader "Gameboy"

{

Properties

{

_MainTex ("Texture", 2D) = "white" {}

_Darkest ("Darkest", color) = (0.0588235, 0.21961, 0.0588235)

_Dark ("Dark", color) = (0.188235, 0.38431, 0.188235)

_Ligt ("Light", color) = (0.545098, 0.6745098, 0.0588235)

_Ligtest ("Lightest", color) = (0.607843, 0.7372549, 0.0588235)

}

SubShader

{

...

}

}

We then need to add these parameters as uniforms to our shader:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Shader "Gameboy"

{

Properties

{

...

}

SubShader

{

...

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _Darkest, _Dark, _Ligt, _Ligtest;

...

}

}

And now we can use these colors in our calculations.

First, let’s find a brightness value of the pixel. Usual pattern in this case is to find a dot product of a pixel RGB value and a Luma vector. Luma vector represents the “weight” of the color on the overall brightness. A tempting thing is to just use a uniform (0.33, 0.33, 0.33) vector for all colors, and it will get us a grayscale image, but this is not how sRGB works. sRGB color requires us to use a (0.2126, 0.7152, 0.0722) vector. It’s still common to see an old and legacy luma vector (0.3,0.59,0.11), (even the ShaderForge uses it), but it’s wrong. It was used for the NTSC RGB color space and it somehow still lives to this day in this form. sRGB requires us to use the brightness vector that I’ve showed earlier. This comparison, as well as other color space brightness vectors can be found here — http://www.brucelindbloom.com/index.html?WorkingSpaceInfo.html

With all that said -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Shader "Gameboy"

{

...

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _Darkest, _Dark, _Ligt, _Ligtest;

float4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

float4 originalColor = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

float luma = dot(originalColor.rgb, float3(0.2126, 0.7152, 0.0722));

...;

}

...

}

Line 10 — just getting a current pixel value Line 11 — calculating pixel brightness (desaturating it)

Now starts the tricky part. We need to posterize our image and reduce the total number of colors to 4. The formula is pretty simple:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Shader "Gameboy"

{

...

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _Darkest, _Dark, _Ligt, _Ligtest;

float4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

float4 originalColor = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

float luma = dot(originalColor.rgb, float3(0.2126, 0.7152, 0.0722));

float posterized = floor(luma * 4) / (4 - 1);

}

...

}

Line 12 — flooring the luma value times number of steps, divided by number of steps minus 1. I deliberately left the math in this verbose form. You can either replace 4–1 with 3, or use another uniform parameter to control the total number of colors.

Now goes the original lerping technique by Taylor Bai-Woo:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Shader "Gameboy"

{

...

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _Darkest, _Dark, _Ligt, _Ligtest;

float4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

float4 originalColor = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

float luma = dot(originalColor.rgb, float3(0.2126, 0.7152, 0.0722));

float posterized = floor(luma * 4) / (4 - 1);

float lumaTimesThree = posterized * 3.0;

float darkest = saturate(lumaTimesThree);

float4 color = lerp(_Darkest, _Dark, darkest);

float light = saturate(lumaTimesThree - 1.0);

color = lerp(color, _Ligt, light);

float lightest = saturate(lumaTimesThree - 2.0);

color = lerp(color, _Ligtest, lightest);

return color;

}

...

}

Three lerps between four colors and in the end we get a colored version of our brightness-polarized pixel value. Lerps in this case are completely discrete and don’t have any semi-tones.

Here’s the full shader code — https://gist.github.com/KumoKairo/2c42db9c4219eb76903831500f1ffa42

Now create a new material named Gameboy, change its shader to Gameboy and link it to a new Material field in your Gameboy C# Script (lot’s of Gameboys, don’t mess it up). You’ve done the same thing with the Identity shader. It will look like this:

The only thing that’s left is to add this material to our pipeline. Change the OnRenderImage function to use this new Gameboy material.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

using UnityEngine;

public class Gameboy : MonoBehaviour

{

public Material gameboyMaterial;

public Material identityMaterial;

private RenderTexture _downscaledRenderTexture;

private void OnEnable()

{

var camera = GetComponent<Camera>();

int height = 144;

int width = Mathf.RoundToInt(camera.aspect * height);

_downscaledRenderTexture = new RenderTexture(width, height, 16);

_downscaledRenderTexture.filterMode = FilterMode.Point;

}

private void OnDisable()

{

Destroy(_downscaledRenderTexture);

}

private void OnRenderImage(RenderTexture src, RenderTexture dst)

{

Graphics.Blit(src, _downscaledRenderTexture, gameboyMaterial);

Graphics.Blit(_downscaledRenderTexture, dst, identityMaterial);

}

}

Line 5 — added a new material field.

Line 26 and 27 — first pass is to blit the Source (render image without effects) into our downscaled texture using our posterize-n-colorize shader. And then we copy this downscaled texture into a fullscreen texture as OnRenderImage function logic requires us.

Done, you’re awesome.

P.S. There are other ways to handle usage of shaders and materials like creating them on the fly at runtime. It’s a good option, but for simplicity’s sake I’ve decided to just make it all as Assets.